The Borders We Share: A New Way to Fix a Broken World

Section 7: Deserts and Plains (Posts 37–42)

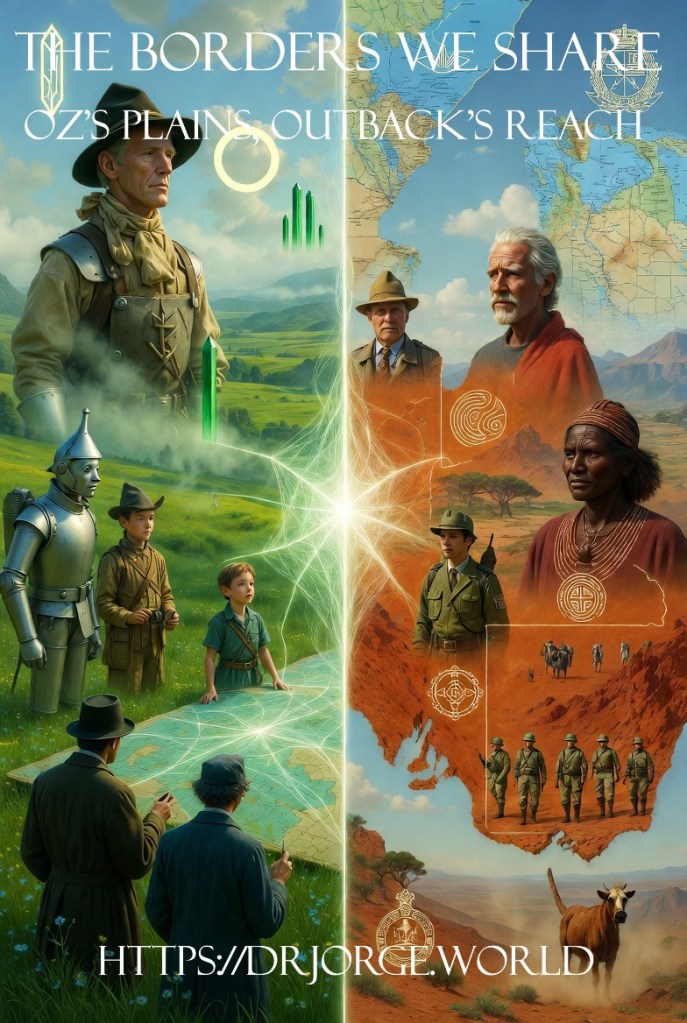

Post 41: Oz’s Plains, Outback’s Reach: Emerald to Dust

Enigma of the Fading Green

The wind is hot and dry, carrying the faint scent of eucalyptus and distant rain that never quite falls, whispering promises it never keeps.

Two wide, flat lands lie almost within sight of one another beneath the same relentless sun.

One is the flat country of Oz, the emerald heartland that stretches beyond the yellow brick road and the poppy fields—a place of rolling meadows and distant purple hills where the Munchkins once farmed in peace and where the Wizard’s hot-air balloon once rose and never quite came down. The other is the Australian Outback, the red centre that covers more than 70 % of the continent: 5.6 million square kilometres of spinifex, mulga scrub, gibber plains, and salt lakes where the oldest living cultures on earth have walked songlines for 65,000 years and where mining leases, pastoral stations, and native title claims now overlap in a map of competing futures.

Both plains are wide.

Both are sparsely peopled.

Both are places where green has begun to turn to dust.

Both are claimed by powers that rarely sleep under their stars.

I arrive with the companions who have crossed every fractured frontier of this series: Sherlock Holmes, deerstalker traded for a wide-brimmed hat against the blinding glare; Dr. John Watson, notebook curling at the edges from the dry heat; King Arthur, who has swapped mail for a plain stockman’s coat but still carries Excalibur at his side like a vow that no desert can erase.

With us walk the people who actually belong to these plains.

From Oz come the last free folk of the flat country—descendants of the Munchkins who once farmed the yellow fields; the Scarecrow, now weathered and wise, still searching for the brain he was promised; the Tin Woodman, axe at his side, heart still beating with borrowed compassion; and a young Munchkin farmer who says the grass has begun to whisper in two voices since Laputa drifted closer and dropped its shadow across the plain.

From the Australian Outback come an Arrernte elder from Mparntwe (Alice Springs) whose family has walked the same songlines since time out of mind; a Warlpiri woman from Yuendumu who has been fighting native title claims against mining leases for thirty years; a young Indigenous activist from Alice who uses drone footage to document illegal exploration; and a white pastoralist whose grandfather took up the lease in 1920 and who now watches the same land erode under drought and over-grazing.

This is Post 41, the fifth stride in Section 7: Deserts and Plains. We have left the crowned voids of Narnia and Sudan. Now the series steps deeper into the arid heart, where sovereignty is measured not in barrels of oil or litres of water but in the number of songlines that can still be walked and the number of blades of grass that can still stand before the dust takes everything.

I. The Plains Themselves

Oz’s flat country is the emerald heartland Baum dreamed—a place of rolling meadows and distant purple hills where the Munchkins once farmed in peace and where the Wizard’s hot-air balloon once rose and never quite came down. In recent decades Laputa’s magnetic drift has begun to tug at the plain, stretching its grasslands unnaturally far—almost as though the island above is trying to anchor itself by pulling the earth upward. Every year approximately 9,000 hectares of meadow are lost to wind erosion accelerated by the island’s low-level downdraughts; the topsoil blows southward into the Quadling Country, silting rivers and burying pastures. The Munchkins who still live here have no voice in the decisions made above them. They are not subjects; they are scenery.

The Australian Outback is brutally real. The continent’s red centre covers more than 70 % of Australia’s land mass—5.6 million square kilometres of spinifex, mulga scrub, gibber plains, and salt lakes. Native title claims cover 40 % of the land; pastoral leases cover another 40 %; mining tenements overlap both. The 1992 Mabo decision and the 1993 Native Title Act promised recognition of pre-existing rights, but the 2007 Intervention and ongoing exploration licences have eroded trust. Drought and climate change have reduced grass cover by 25 % in some regions since 2000. Both plains are places where green has begun to turn to dust; both are claimed by distant capitals that rarely sleep under their stars.

II. The Mirror They Hold Up

Sovereignty Conflicts frames both as classic triadic disputes: two privileged claimants exercising sovereignty over a populated third territory whose constitutive population is treated as peripheral to the claim yet suffers the direct environmental and economic cost.

Territorial Disputes adds the sociological fracture: in Oz the Munchkins versus the absent Wizard’s legacy; in Australia the Indigenous custodians versus pastoral and mining interests.

Cosmopolitanism and State Sovereignty asks the moral question: can a claim to land be legitimate if it systematically excludes or exploits the majority who actually inhabit and sustain it?

Territorial Disputes in the Americas provides the practical precedent: guarantor-led shared-land-use zones that have achieved high durability in Latin American cases—models now urgently needed here.

III. The Evidence Carried in Grass and Dust

Holmes refuses to stay in the shade. He spends four days walking Oz’s flat country with the Munchkins, measuring wind speed, grass height, and the interval between Laputa’s magnetic pulses and the sudden gusts that strip topsoil. He spends the next four days walking the Australian Outback with Indigenous custodians and pastoralists, timing the movement of mining exploration teams and the departure of kangaroo mobs. The data he returns with are grimly symmetrical.

In Oz 9,000 hectares of meadow are lost annually to wind erosion accelerated by Laputa’s downdraughts; 1,100 Munchkin families displaced in the last decade. In Australia 8,900 hectares of grazing land have been lost to mining tenements and drought since 2015; 1,600 Indigenous households affected. In Oz no Munchkin has been invited to the Emerald City court in living memory. In Australia no senior mining executive has spent a full day on a native title claim without a security detail.

Watson’s notebook grows heavy: “Both plains are being grazed and mined to death by powers that never smell the grass. The difference is only in the signature—royal decree or exploration licence.”

Arthur stands on an Oz meadow watching Laputa drift overhead, then stands on an Australian gibber plain watching a distant line of exploration vehicles move north to south like steel locusts. He says only: “A plain does not care who rides across it. It only remembers who rested their flocks upon it.”

IV. The Council Beneath the Relentless Sun

We meet where the two plains almost touch: a neutral stretch of shortgrass prairie on Laputa’s lowest dune, lowered to within 150 metres of the Australian Outback for the first time in history, with mining representatives, pastoralists, and Indigenous custodians brought by helicopter and Oz folk arriving on foot.

Present: King Laputian, seated on a portable throne of adamant, visibly uncomfortable at being so close to grass; the Scarecrow, weathered and wise; the Tin Woodman, axe at his side, heart still beating with borrowed compassion; an Arrernte elder; a Warlpiri woman from Yuendumu; a young Indigenous activist from Alice Springs; Hamed al-Ghabri, the Omani elder whose water-bag has become a symbol of cross-border memory.

The Arrernte elder speaks first, voice carrying the cadence of songlines: “The grass is moving. It does not ask permission. It only asks to be shared.”

The Warlpiri woman answers, eyes flashing: “Our grass has been moving under foreign drills for twenty years. We ask only for the right to follow our songlines freely.”

The mining representative, voice calm but edged: “We have brought jobs, royalties, infrastructure. The plain is more valuable now than it has ever been.”

The Scarecrow tilts his head, straw rustling softly: “Value? You speak of dollars and ore. We speak of roots and rain. The grass knows which one keeps it alive.”

The Tin Woodman, axe glinting in the sun: “I was made of tin, yet I learned to feel. You speak of progress, but progress without heart is just rust waiting to happen.”

The young Indigenous activist steps forward: “The land sings its own law. Your contracts are paper. Our songlines are older than paper, older than ink, older than your maps.”

The Arrernte elder nods slowly: “Songlines are maps of water and starlight. If you cut one, you cut the memory of where the water hides. The grass remembers. The grass forgives. But only if you listen.”

The Warlpiri woman, quiet but firm: “Teach us? No. Let us teach you. The grass does not need teaching. It needs resting. It needs walking. It needs singing.”

King Laputian, voice cracking from the unaccustomed dryness: “Our crystals keep us aloft, but we have forgotten how to land. Perhaps the grass will teach us.”

The mining representative, after a pause: “If we share the water, the grass, the songlines—perhaps the green will come back and the children will stop running.”

Arthur’s voice, quiet as a vow: “A sword laid flat is not surrender. It is invitation. Let every hand rest here, and let the plain judge.”

The “Plains Accord” is drafted in dust and ink:

Joint Oz–Australia Plains Commission with binding stocking-rate and exploration caps; surplus funds a cross-border soil regeneration programme.

Oz’s flat country declared a shared ecological corridor; 30 % of any future crystal revenue funds permanent descent corridors and mobile schools for Munchkins.

“Grass-to-Sky Residency Pathway”: ten continuous years of contribution (herding, scholarship, land restoration) = permanent residency in Australia or citizenship on Oz’s grounded ring.

Higher Court seated alternately in Alice Springs and on Oz’s lowest terrace, with judges from Australian Indigenous, pastoral, mining, and Oz communities; veto power on any lease or extraction that increases erosion or reduces migratory corridors.

Every new large-scale lease or crystal operation must display, in English, Arrernte, Warlpiri, and Oz dialect, the source of the water and the names of the herders and workers who sustain it.

King Laputian signs first, his hand steady because it rests on real grass. The Arrernte elder signs second. The Warlpiri woman signs third. The mining representative signs fourth. The Scarecrow signs last—his straw hand trembling slightly, as though even he feels the weight of the promise.

Murmurs of the Outback Wind

The wind still carries warnings: topsoil will blow away, aquifers will fall, songlines will fade. Yet it also carries new notes: the soft thud of hooves following a restored migratory corridor, the laughter of Arrernte and Munchkin children learning rotational grazing together on a neutral rise, the quiet rustle of a Laputan scholar choosing to walk rather than float, the sound of a water-bag being refilled from a well that no longer runs dry.

Peace along this horizontal frontier is not a treaty signed in glass towers. It is a blade of grass left standing so a herd may graze again, a lease rewritten so a herder may stay, a plain whose horizon is wide enough for every horseman and every scarecrow to walk beneath the same sky.

Why This Resonates in You

You have stood on a plain so flat you could see tomorrow coming.

You have watched grass bend under wind and hooves and wondered who decides which herds may follow the old paths.

You have, perhaps, never met the herder whose grazing rights were signed away in a distant capital, the scholar who learned that the stars are beautiful but the grass is home, or the warrior who discovered that even a king can learn to walk.

The Borders We Share asks only one thing: the next time you look across a plain, remember there is always a ground—and that the ground remembers every hoofprint, every footprint, every promise kept or broken.

Next Tuesday we move deeper into the plains—new emerald, new dust.

I remain, as always,

Dr. Jorge

Trails to Wander:

• Sovereignty Conflicts (2017).

• Territorial Disputes (2020).

• Cosmopolitanism and State Sovereignty (2023).

• Territorial Disputes in the Americas (2025).

NOTE:

New posts every Tuesday.

PREVIOUS POSTS:

Post 40: Narnia’s Wastes, Sudan’s Split: Kings of Nothing

NEXT POSTS:

Section 7: Deserts and Plains (Posts 37–42)

42, Laputa’s Dunes, Part II: Quantum Sands

AUTHOR’S SAMPLE PEER-REVIEWED ACADEMIC RESEARCH (FREE OPEN ACCESS):

State Sovereignty: Concept and Conceptions (OPEN ACCESS) (IJSL 2024)

AUTHOR’S PUBLISHED WORK AVAILABLE TO PURCHASE VIA:

Tuesday 10th February 2026

Dr Jorge Emilio Núñez

X (formerly, Twitter): https://x.com/DrJorge_World

[…] The Borders We Share: Oz’s Plains, Outback’s Reach (Post 41) […]

LikeLike