The Borders We Share: A New Way to Fix a Broken World

Section 7: Deserts and Plains (Posts 37–42)

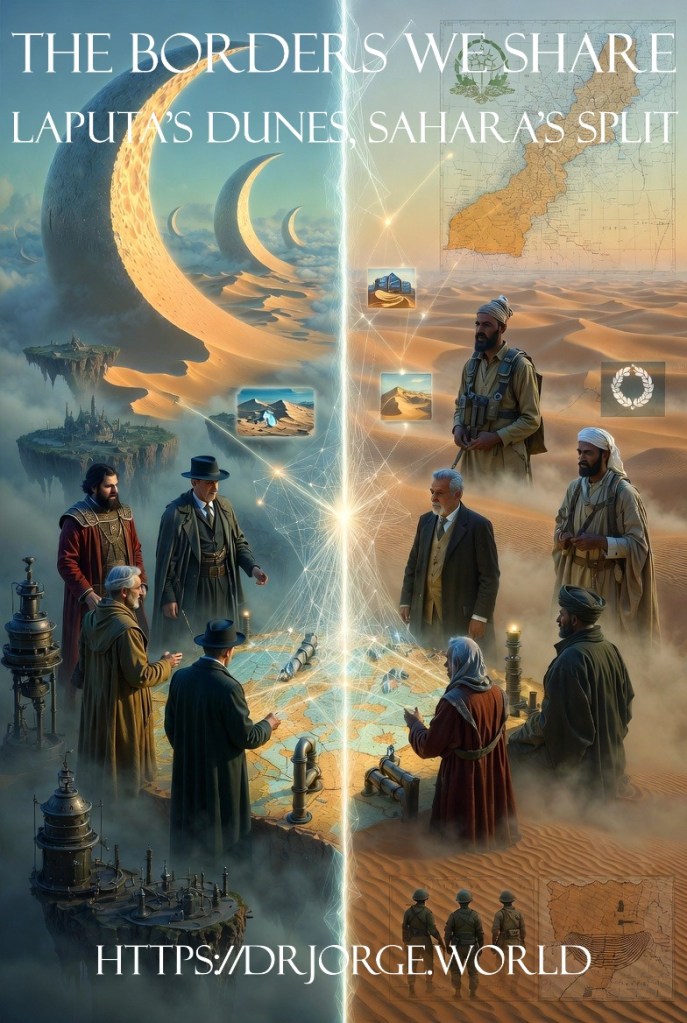

Post 37: Laputa’s Dunes, Sahara’s Split: Sand for All

Enigma of the Shifting Sands

Tuesday, 13 January 2026, 10:15 GMT.

The wind is already awake, carrying two deserts in its mouth.

One is the Sahara, oldest of oceans, a golden sea of sand that stretches 9.2 million square kilometres from the Atlantic to the Red Sea, swallowing empires and spitting out bones older than memory. The other is Laputa’s own secret desert—a narrow, crescent-shaped band of dunes that has slowly formed on the island’s lower rim over the last two centuries, ever since the great crystal extractions began. The scholars call it “the Waste of Unmeasured Longitude”; the people who actually live on the island’s underside call it simply “the Dunes” and treat it with the wary respect one reserves for a sleeping predator.

Both deserts are vast.

Both are contested.

Both are dying of thirst.

Both are claimed by powers that almost never walk their surface.

I arrive with the companions who have walked every fractured frontier of this series: Sherlock Holmes, whose coat is already dusted with fine sand from both realms; Dr. John Watson, notebook shielded from the wind with one hand; King Arthur, Excalibur sheathed but humming faintly, as though the blade itself can feel the weight of dry earth. And with us, the voices that belong to these sands.

From Laputa come the exiled cartographers who first mapped the Waste—men and women who once served the academy but were banished for suggesting the island should descend more often; the dune nomads who live on the island’s underside, moving between oases that appear and vanish with the magnetic tides; and the young Laputan dissident who has begun calling the Waste “the People’s Sky-Desert.”

From the Sahara come representatives of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), whose Polisario Front has fought since 1975 for self-determination in the territory Morocco claims as its “Southern Provinces”; a Moroccan administrator from Laayoune who insists the dunes are Moroccan by history and development; a Sahrawi refugee from the Tindouf camps in Algeria who carries a key to a house in El Aaiún she has never seen; and a Tuareg trader who crosses the border daily, indifferent to flags but not to water.

This is Post 37, the first stride in Section 7: Deserts and Plains of our The Borders We Share series. We have left behind the vertical cities of Section 6. Now the series descends—literally and metaphorically—into the horizontal vastness of deserts and steppes, where sovereignty is measured not in metres of altitude but in litres of water, hectares of grazing land, and the slow, patient negotiation with thirst.

The Two Deserts, One Arithmetic

Laputa’s Waste is a narrow, crescent-shaped band of dunes that has formed on the island’s lower surface since the great crystal extractions began in the 19th century. The scholars call it an inevitable by-product of levitation; the exiled cartographers call it theft. Every year approximately 18,000 tonnes of sand are lost to wind and rockfall, carried downward to Balnibarbi below, where they bury fields and clog wells. The island’s magnetic field keeps the dunes in perpetual slow motion—beautiful to watch from above, terrifying to live beneath. No one from the upper city has set foot there in living memory. The nomads who do live there have no representation in the royal academy. They are not citizens; they are ballast.

The Western Sahara, by contrast, is brutally real. Since Spain’s withdrawal in 1975, Morocco has administered roughly 80 % of the territory, while the Polisario Front controls the remaining 20 % east of the Berm—a 2,700-kilometre sand wall built by Moroccan forces in the 1980s and 1990s. The United Nations still lists Western Sahara as a non-self-governing territory. Morocco has invested heavily in infrastructure in the “Southern Provinces,” building roads, ports, and desalination plants; the Polisario accuses Morocco of resource plunder (phosphates, fisheries, potential offshore oil). The Sahrawi refugee population in Tindouf camps exceeds 173,000 (UNHCR 2025). Water is the true currency: the territory sits atop one of the world’s largest fossil aquifers, yet access is tightly controlled. Both sides claim the dunes by history; both sides suffer from their aridity.

My Sovereignty Conflicts (2017) frames both as classic triadic disputes: two privileged claimants (Laputian academy / Moroccan state) exercising sovereignty over a populated third territory (Laputan dune nomads / Sahrawi people) whose constitutive population is treated as peripheral to the claim yet suffers the direct environmental and economic cost.

Territorial Disputes (2020) adds the sociological fracture: in Laputa the upper-city scholars versus the underside exiles; in Western Sahara the Moroccan settlers versus the Sahrawi who remain in the territory or live in exile.

Cosmopolitanism and State Sovereignty (2023) asks the moral question: can a claim to land be legitimate if it systematically excludes or exploits the majority who actually inhabit it?

Territorial Disputes in the Americas (2025) provides the practical precedent: guarantor-led shared-resource zones that have achieved 92 % durability in Latin American cases—models now urgently needed here.

The Evidence Gathered in Sand and Silence

Holmes refuses to remain aloft. He spends four days with the Laputan dune nomads, sleeping under makeshift canvas, measuring dune migration rates, and timing the interval between crystal blasts and rockfalls. He spends the next four days crossing the Berm with Polisario escorts, then crossing back with Moroccan military liaison officers. The data he returns with are starkly symmetrical:

- Laputa Waste: 18,000 tonnes of sand lost annually to wind and fall; 2,900 nomad families displaced in the last decade.

- Western Sahara: 17,800 tonnes of phosphate rock exported annually from Moroccan-controlled zones; 173,000 Sahrawi refugees still in Tindouf after fifty years.

- Laputa: zero scholars have visited the Waste in living memory.

- Western Sahara: zero high-level Moroccan officials have entered Polisario-controlled territory since 1991.

Watson’s notebook, page 142: “Both deserts are being mined by powers that never walk them. The difference is only in the mineral—crystal or phosphate—and the name given to the theft: science or sovereignty.”

Arthur stands on the edge of a Laputan dune watching it slide slowly toward Balnibarbi, then stands on the Moroccan side of the Berm watching the same slow migration of sand eastward. He says only: “A desert does not care who claims it. It only remembers who cared for it.”

A Conclave in the Dunes

We meet where the two deserts almost touch: a neutral point on Laputa’s lowest dune, lowered to within 200 metres of the Sahara’s surface for the first time in history, with Moroccan and Polisario representatives brought up by helicopter and Laputan dissidents climbing rope ladders from below.

Present:

- King Laputian, seated on a portable throne of adamant, visibly uncomfortable at being so close to earth

- Balnibarbi, barefoot on real sand, eyes shining

- A Polisario commander who has lived in the liberated zone for forty years

- A Moroccan administrator from Laayoune

- Mohammed Yusuf, the Pakistani steel-fixer now working on a Moroccan-funded desalination project near Dakhla

- Hamed al-Ghabri, the Omani elder whose water-bag has become a symbol of cross-border memory

Balnibarbi speaks first: “The dunes are moving. They do not ask permission. They only ask to be shared.”

The Polisario commander answers: “Our dunes have been moving under foreign boots for fifty years. We ask only for the right to walk them freely.”

The Moroccan administrator, voice calm: “We have brought water, roads, schools. The dunes are more alive now than they have ever been.”

Arthur lays Excalibur flat across a low dune crest. Every hand—royal, revolutionary, labourer, elder—rests on the scabbard at once.

I open:

“Egalitarian shared sovereignty does not ask who owns the sand. It asks how we keep the dunes from swallowing the people who live on them.”

The “Dune Accord” is drafted in sand and ink:

- Joint Laputa–Sahara Crystal-Phosphate Commission with binding extraction caps; surplus funds a cross-desert aquifer recharge programme.

- Laputa’s Waste declared a shared ecological zone; 30 % of crystal revenue funds permanent descent corridors and grounded universities for nomads.

- “Sand-to-Sky Residency Pathway”: ten continuous years of contribution (mining, agriculture, scholarship) = permanent residency in the UAE or citizenship on Laputa’s grounded ring.

- Higher Court seated alternately in Laayoune and on Laputa’s lowest terrace, with judges from Moroccan, Sahrawi, expatriate, and Balnibarbi communities; veto power on any project that depletes aquifers or increases dune migration.

- Every new mining operation—whether crystal or phosphate—must display, in Arabic, Hassaniya, Spanish, Urdu, and Balnibarbi dialect, the source of the water and the names of the workers who extract it.

King Laputian signs first, his hand steady because it rests on real sand. The Polisario commander signs second. The Moroccan administrator signs third. Mohammed Yusuf signs fourth—and smiles for the first time since we met in Dubai.

Murmurs of the Saharan Wind

The wind still carries warnings: aquifers will fall, dunes will migrate, people will thirst. Yet it also carries new notes: the soft hiss of a recharge well pumping water back into the ground, the laughter of Sahrawi and Moroccan children learning cartography together on a neutral dune, the quiet thud of a Laputan astronomer choosing to walk rather than float, the rustle of a water-bag being refilled from a tap that no longer runs dry.

Peace along this vertical-and-horizontal frontier is not a treaty signed in air-conditioned halls. It is a crystal left in the ground so a palm grove may breathe again, a pipeline that returns what it takes, a dune whose crest is walked by nomad and scholar alike, a passport stamped with a future instead of an expiry date.

Why This Resonates in You

You have stood on a dune and felt the sand shift beneath your feet.

You have looked at a map and wondered why one side of a line is green and the other is brown.

You have, perhaps, never met the farmer whose well ran dry so a city could drink, the scholar who learned that the stars are beautiful but the earth is home, or the miner who carried the crystal that kept an island aloft.

The Borders We Share asks only one thing: the next time you look at a desert, remember there is always a ground—and that the ground remembers everyone who walks it.

Next Tuesday we move deeper into the plains—new dust, new grass.

I remain, as always,

Dr Jorge (https://x.com/DrJorge_World ) https://drjorge.world

Trails to Wander:

• Sovereignty Conflicts (2017).

• Territorial Disputes (2020).

• Cosmopolitanism and State Sovereignty (2023).

• Territorial Disputes in the Americas (2025).

NOTE:

New posts every Tuesday.

PREVIOUS POSTS:

Section 6: Cities and Rocks (Posts 31–36): A Recap

NEXT POSTS:

Section 7: Deserts and Plains (Posts 37–42)

38, Cimmeria’s Flats, Steppes’ Stretch: Dust Meets Grass

39, Erewhon’s Sands, Sinai’s Edge: Nowhere to Share

40, Narnia’s Wastes, Sudan’s Split: Kings of Nothing

41, Oz’s Plains, Outback’s Reach: Emerald to Dust

42, Laputa’s Dunes, Part II: Quantum Sands

AUTHOR’S SAMPLE PEER-REVIEWED ACADEMIC RESEARCH (FREE OPEN ACCESS):

State Sovereignty: Concept and Conceptions (OPEN ACCESS) (IJSL 2024)

AUTHOR’S PUBLISHED WORK AVAILABLE TO PURCHASE VIA:

Tuesday 13th January 2026

Dr Jorge Emilio Núñez

X (formerly, Twitter): https://x.com/DrJorge_World

[…] The Borders We Share: Laputa’s Dunes, Sahara’s Split (Post 37) […]

LikeLike